Pennsylvania Protestors

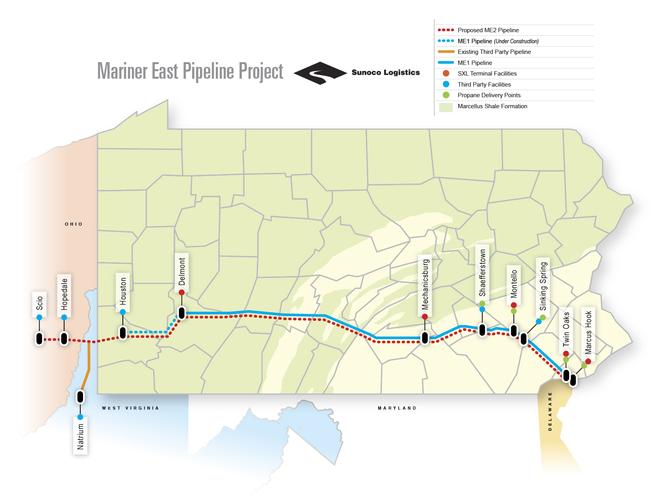

The 350-mile Mariner East II pipeline would carry fracked gas liquids across the state, but a new protestor encampment wants to stop it.

It’s easy to miss the entrance to Camp White Pine, on Ellen Gerhart’s Huntingdon County, Pennsylvania property. The narrow, wooded driveway has no house number visible from the road, just a yard sign reading “No Trespassing – No Surveying – No Mariner East Pipeline “.

Mariner East II is a project of Sunoco Logistics (which merged this year with Energy Transfer Partners, the company that built the Dakota Access Pipeline). The 350-mile pipeline would carry fracked gas liquids from the Marcellus and Utica shales to an energy terminal near Philadelphia. The Gerharts and supporters started the encampment over a year ago, when they began occupying several tall trees in the pipeline’s path to prevent them from being cut down.

I drove to the Gerharts’ 27-acre property on a recent sunny morning and found the camp eerily deserted. With no cell service, I wandered around the yard of the one-story rancher, looking for someone to announce my presence to. By the house were some tents, an old trailer, and a coop with hens and a rooster. A TV was audible from the front door, but no one answered the buzzer. Down a small wooded slope, I found a full outdoor kitchen stocked with supplies, more tents, and a shelter with climbing equipment dangling from the walls; the site looked a bit like an abandoned rock-climbing camp.

“We’ve had our sense of security violated for a long time now.”

Suddenly, a black dog bolted out of the woods towards me, followed by two people. One is Elise Gerhart, Ellen’s daughter, carrying a walkie talkie.

“Apparently several people were aware you were here, but I wasn’t one of them,” Elise says. The protesters have been on edge for over a year now, ever since a judge granted Sunoco permission to use eminent domain to access 3 acres of the Gerharts’ property.

A Sunoco representative visited the Gerharts in the spring of 2015 to negotiate a contract to use three acres for the pipeline. After a brief negotiation, the Gerharts refused to sign, because they felt that the $30,000 the company ultimately offered was not enough compensation for the environmental damage and safety risks they believe the pipeline will create. The pipeline would run under a pond and wetlands on the property; the pond feeds into a creek, which feeds into the Juniata River. The Juniata is a tributary of the Susquehanna River, the longest river on the East Coast.

The Middletown Coalition for Community Safety adapted the federal government’s formula for calculating a methane gas pipeline’s potential impact radius (PIR) to estimate that Mariner East II’s PIR is between 1100 and 1150 feet. Part of the pipeline construction site is less than 500 feet from the Gerharts’ home. In the unlikely event of an explosion, anyone within the blast zone would be killed immediately.

In March 2016, workers used chain saws to begin clear-cutting trees. Protesters climbed into the elaborate tree-sits they’d constructed in several of the trees to prevent them from being cut down. The trees are tied to each other with ropes, making it difficult to cut down any of the trees without endangering the other tree-sitters. Elise spent about 6 days in a tree over the course of two weeks. “It was cold and windy, and sometimes wet,” she says.

Part of the pipeline construction site is less than 500 feet from the Gerharts’ home. In the unlikely event of an explosion, anyone within the blast zone would be killed immediately.

We walk through the woods, stopping at a clearing near Sunoco’s easement. A tree-sitter waves from a platform about 30 feet up in the tree; meanwhile, another participant uses ropes to send food up to the sitters.

Camp White Pine protesters are also concerned about drinking water. The Gerharts and their neighbors use private wells; earlier this year, water from more than a dozen wells in eastern Pennsylvania was contaminated with sediment after Sunoco’s horizontal drilling affected a nearby aquifer.

Sunoco plans to put a horizontal drill pad on the Gerhart property to drill underneath a stream. In an email, a spokesman for ETP says they’ve taken additional measures to protect well water since the incident, including testing water from all wells within 450 feet of a horizontal directional drill; previously, they only tested wells within 150 feet. Some new measures have been implemented as a result of a settlement with the Environmental Hearing Board after the incident, the spokesman said. He also noted that test results of water from affected wells found it remained safe to drink, despite the sediment.

“If they’ve only drilled 25 percent and they’re already contaminating water, what happens when they’ve drilled 100 percent? People will lose their access to drinking water, and we don’t want to be one of those people,” Elise says. “We want the right to just say, given the history, given the facts, we don’t want that to happen to us.”

A judge eventually granted an injunction barring the Gerharts from setting foot on Sunoco’s easement on their property. Ellen has been arrested three times; once, Ellen says, she sat alone in a cell for three days without a phone or access to a lawyer. She was eventually released on $5,000 bail.

“If they’ve only drilled 25 percent and they’re already contaminating water, what happens when they’ve drilled 100 percent?”

Sunoco Logistics says that the Mariner East project benefits Pennsylvania; it predicts the project will generate 300-400 permanent jobs, and contribute more than $100 million to the state’s economy each year.

But local opponents, including the non-profit Food and Water Watch, say the project was never meant to serve Pennsylvanians. In order to receive permission to use private property under eminent domain, Sunoco had to demonstrate that the project serves a public interest. Much of the gas that Mariner East II would transport is slated for export to Europe, but Sunoco added three propane distribution points in Pennsylvania after the York County Court of Common Pleas questioned whether the project served the public interest. Sunoco claims the terminals were added after the 2014 polar vortex demonstrated a greater need for petroleum heat in the state.

The Philadelphia Inquirer reports that the European petrochemical company Ineos has spent over $1 billion on a system to transport ethane from Sunoco’s Philadelphia facility, where Mariner East terminates, to plants in Norway and Scotland. Ineos has posted multiple statements about the partnership on their website. One post from 2016, written after the first shipment of shale gas left the Sunoco terminal for Europe, proclaimed: “This is the first time that US shale gas has ever been imported into Europe and finally gives the continent the chance to benefit from US shale gas economics.”

“Ineos proudly announces that they’re bringing shale gas to Europe, yet Pennsylvania landowners are being told they need to sacrifice their property for the public good,” Elise says. The Gerharts and other landowners have challenged the eminent domain ruling on those grounds, claiming the Mariner East project does not meet the criteria of public interest.

Camp White Pine’s participants have been locked in this protracted battle for over a year, and at times it’s taken an ugly turn. Elise says they’ve received multiple death threats, which she believes were inspired by social media posts like those on a Facebook page called PA Progress, which published a video portraying the White Pine protesters as dangerous, and encouraging residents to report suspicious activity to the Huntingdon County sheriff. And The Intercept reported that the same actor appeared under a different alias in another video with a similar message on a page called “Louisiana First”. Energy Transfer Project has active pipeline projects in both states.

Adding to the tense atmosphere of the camp, participants feel they’re being watched.

“We know someone is surveilling us…sometimes four or five times a day we’ll get a helicopter overhead, circling. We’ve had drones fly into the property really invasively… we have trucks sitting across the road facing our property watching the driveway… I’ve had my picture taken by someone while I was at work. They posted it on PA Progress and claimed that I’m trying to destroy my own community,” Elise says.

The ETP spokesman says it is standard procedure for construction companies to use helicopters to survey a pipeline construction corridor. He also confirmed that ETP has flown a drone over Camp White Pine. Pulling out of the camp’s driveway, I spotted a large blue truck parked on a dirt patch atop a hill across the road, facing the camp.

But the length of the battle itself also gives the Gerharts hope. “This is a very small operation, with very limited funds from donations – yet we’ve been able to maintain this stand for over two years, resisting this. They still haven’t put that pipeline in,” Elise says.

“These companies think they can take people’s land and push all the costs onto taxpayers, and yeah – we’re done with that.”