George Gittoes

– Artist’s Website –

Article by Sune Engel Rasmussen for Good Weekend, The Age

Conflict and brutality have formed the work of Australian artist George Gittoes, who this year is the recipient of the Sydney Peace Prize.

At dusk, a blue-tinged light envelops the mountain ridges outside Jalalabad, in eastern Afghanistan. The evenings here would be mostly quiet were it not for the occasional crackling of gunfire and the buzz of unmanned drones traversing the sky like huge mechanical bugs. “This is Taliban Central,” George Gittoes says, not without a certain relish, as we drive through a small village on the edge of town in a battered Toyota Corolla. The Australian artist and filmmaker brands himself an “edge walker” and compares his own courage to that of soldiers.

At a rickety roadside stall, three young men are slurping hot soup, surrounded by children playing in the dirt. Boys knock metal wheels around with sticks, whirling up spirals of dust, and girls with scarecrow-red hair and blue dresses eye us suspiciously. In a green field, farmers discuss the coming cauliflower harvest.

“I liken this to the Great Barrier Reef,” says Gittoes. “I could spend hours here just watching. Everything that passes by is just so beautiful. So exotic.”

It was from Jalalabad that a team of US Navy SEALs four years ago departed on a kill mission in two Black Hawk helicopters headed for Osama Bin Laden’s compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan. In the same year, 2011, Gittoes, who’d set up mobile art studios in conflict zones around the world for three decades, decided to make Afghanistan his new base.

With the help of his partner, Hellen Rose, a singer and actress from Sydney, Gittoes has started a film production company in a walled compound named the Yellow House, after the Sydney art collective he helped found in the 1970s. The house serves as a painting studio and movie workshop for local talents, street kids and outcasts who swarm the house at all hours of the day.

Later this year, Gittoes will receive the Sydney Peace Prize, Australia’s only international peace award, “for exposing injustice for more than 45 years as a humanist artist, activist and filmmaker; for his courage to witness and confront violence in the war zones of the world; for enlisting the arts to subdue aggression and for enlivening the creative spirit to promote tolerance, respect and peace with justice”.

In Jalalabad, Gittoes has survived war, death threats and a pet monkey that went mad, murdered all his other pets, and which he eventually had to hunt down and shoot. And he has seen sides of the war in Afghanistan that few foreigners in the country ever get to witness.

“I’ve been to quite a few places that have been hit by drones and it’s nasty, you know,” Gittoes says. “Just because someone in a clean environment somewhere is operating a video console doesn’t make it any less nasty than chopping someone’s head off.”

As an artist, Gittoes feeds off the horrors of humanity from which most people prefer to avert their eyes – or which they simply cannot comprehend. “The world hasn’t been allowed to forget what happened to the Jews in Germany, so why should they be allowed to forget what happened to the Africans in Rwanda?” he asks.

He paints to record the dark sides of history and his works are ghoulish: Captain America eaten by rats in Iraq. A boy standing in front of a cage full of skulls. A Rwandan woman with her nose and breast hacked off.

“Matisse said that art should be something you could lean back in an arm chair and relax to,” Gittoes says with a wry smile that suggests he doesn’t quite agree. “Your art is more like an electric chair,” suggests Andrew Quilty, the photographer. “Yes, electric chair. Like Guantanamo or something.”

Meet George Gittoes. If you haven’t heard of him, well, you should have. At least that’s what he said the first time I met him, at the Australian embassy in Kabul, when a female journalist asked him what kind of art he did. “Darling, you should know who I am,” he said.

And he’s not the only one who thinks so. “Gittoes is not particularly well known but he should be,” says David Hirsch, chair of the Sydney Peace Foundation, which picked him from a field of 50 candidates.

“He represents a very good side of Australians,” says Hirsch. “Australians have become used to seeing themselves as insular and selfish. He is quite the opposite. Australians should see some of their better selves in a character like his. He is using art as a way of tapping into the universal creativity of people. We see his work in Afghanistan as an example of using the arts to enable people, to lift people up, to liberate them.” This is the first time, Hirsch says, that an artist has been awarded the prize. Previous recipients include South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu, US scholar and activist Noam Chomsky, and Australian journalist John Pilger.

But Gittoes also has a knack for rubbing many people up the wrong way. He traffics in swaggering self-praise and his work is often crude and unsubtle. A gallery owner who used to work with Gittoes once told him that Margaret Olley, the late matriarch of Australian painting, had vehemently protested at him exhibiting Gittoes’ work.

Charles Green, head of art history at Melbourne University, who has just completed a research project on artists’ engagement with war, says Gittoes paints with a rawness that is “carefully calculated and monumental” and that his films are “hypnotic”.

Gittoes witnessed carnage and massacres in Rwanda and Somalia. He saw the conflicts in Cambodia, Bosnia, Yemen and the Congo. In 2005, he released the Iraq war documentary, Soundtrack to War, pieces of which were used in Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11. In a review, film critic Margaret Pomeranz described Gittoes work as “intensely human, vulnerable and insightful”.

“George Gittoes is completely crazy-brave,” Green says. “I am completely amazed he survives.”

Born in Sydney in 1949, George Gittoes grew up in a middle-class family in the suburb of Rockdale. His mother was a ceramicist and his father a public servant. He discovered an early affinity with Islamic art and literature in high school, reading the poet Omar Khayyám. Studying fine arts at the University of Sydney, he fell in love with the abstract art of Piet Mondrian and Kazimir Malevich, but was the only one among his fellow students who had a go at abstract painting. A visit to the school by American art critic Clement Greenberg was a defining moment. “He said, ‘Shit, man, these are good, you should come to America. This place is dead,’ ” Gittoes recalls. So he dropped out of university and worked as a surveyor’s assistant on the Cahill Expressway until he could move to the United States.

In New York, Gittoes continued to study and learnt how to photograph and shoot 16mm film. His ties to the city remain strong. “In New York, people get what I do. In Australia, they don’t,” he says. Aside from Arthur Boyd, who comes close, he continues, “Australia has never produced a great painter. I’m not saying I will be. I haven’t painted enough. I have done too many other things.”

The inbred nature of Australian art hasn’t changed since he was a young artist, he says. He blames galleries and art dealers for stunting artistic development. “Dealers in Australia, when they see an artist who does something they like, they get them to stick to it.” As a result, he says, “Everyone sells out.”

When he returned to Australia in 1970, Gittoes established the Yellow House in Sydney’s Potts Point with a group of other artists, including Martin Sharp, but it wasn’t until 1986 that Gittoes became overtly political in his work. In Nicaragua he filmed Bullets of the Poets, a documentary about six women who’d fought in the Sandinista revolution. But nothing seems to have made a deeper imprint on Gittoes than his time in Rwanda during the 1995 Kibeho massacre, where soldiers of the Rwandan Patriotic Army killed a reported 4000 people in a refugee camp. It was in Rwanda that Gittoes produced some of his most evocative work and it is a place he continues to return to in conversation. “There’s nothing worse I have experienced in my life than when I was in Kibeho, when thousands of people were slaughtered with machetes in front of me,” he says.

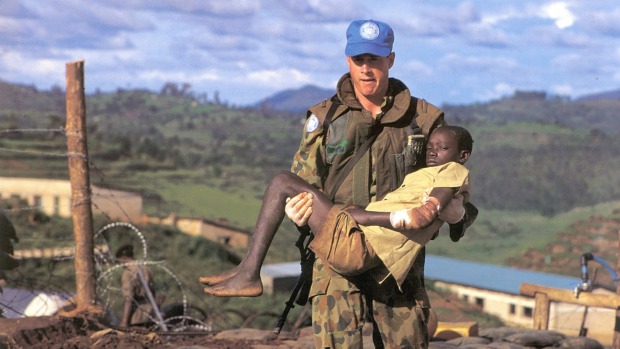

It was also in the wake of Rwanda that Gittoes realized his art didn’t change things the way he’d hoped. One of the strongest images he captured from that time was his photograph of SAS trooper Jonathan Church carrying a Rwandan child who survived the massacre. His career has taught him that images, no matter how graphic, don’t change government policies. Projects on the ground, like the Yellow House, are more effective.

With age, Gittoes has become more involved in outright activism. He joined the Occupy Wall Street movement and has thrown his lot behind the most prominent dissident of the internet age. “One of my newest and best friends is Julian Assange,” he says, pulling out a photo of the two taken inside London’s Ecuadorian Embassy, where Assange has taken refuge for more than two years. “I reckon he’s just f…ing great. He’s the greatest living Australian since Ned Kelly.”

For the first time, Gittoes now lives in a conflict zone with a partner. “Hellen is the only woman I have let come with me. Or, I don’t let her, she just comes,” he smiles. The couple don’t have children, but Gittoes has a son and a daughter, both in their late 20s, from a previous marriage: Harley is an environmental engineer and Naomi is an underwater diver and artist.

“It was hard for me to live here,” Hellen says. “It’s apartheid against women here.” She came, she says, because she couldn’t stand it if something happened to Gittoes and she wasn’t here. “I’m a staunch feminist. My friends say, ‘Hellen, how can you wear the burqa?’ I can, because I take it off: they can’t. I’ll wear it if I can help women get back to where they were in the ’70s.” She runs workshops for women, teaching them how to make documentaries and broadcasts.

At 65, Gittoes looks like an ageing sufi mystic turned country rocker. His beard is white and his hair is long and greying. His hands are big and craggy. He shuffles around the garden in a hoodie and paint-stained Crocs. Walking the streets of Jalalabad or scaling the hills outside town, he wears worn-out black Nikes under a traditional Afghan shalwar kameez. His black socks have kangaroos on them.

Gittoes has a short fuse and is often intolerant of other people’s opinions and, it seems, of most other artists. There is no doubt around the Yellow House that his decisions are not up for discussion. A straight-talker, he can sound smugly self-important. Afghanistan’s new president, Ashraf Ghani, for instance, is “one of the most original thinkers you ever heard”; Australia’s Governor-General Peter Cosgrove, on the other hand, is “a dumb-ass”. As for post-traumatic stress disorder, “Weak people get it. Strong people don’t.”

At the same time, Gittoes is a gracious host who serves the visiting journalist and photographer hot porridge with bananas and cashews in bed at 8am. He is grandfatherly affectionate with the street kids and actors around the Yellow House and rubs the neck of a taxi driver as he tries to make conversation despite hardly speaking a word of Pashtu.

Gittoes is probably the only Westerner in all of eastern Afghanistan who doesn’t live in a compound behind fences and barbed wire. The Australian Embassy, which also helps to fund some Yellow House activities, recently cancelled a visit because even a few hours in Jalalabad were deemed too risky for the diplomats. In fact, Quilty and I are the first foreigners to visit the Yellow House.

It draws a squad of kids and outcasts that Gittoes has taken under his wing. They include four street boys who make a living waving metal cans of smoking coals over people’s cars, a superstitious practice meant to chase away spirits. Gittoes calls them the Ghostbusters. Another trio of kids, the Ice-Cream Boys, are shooting their own movie. One’s father is a drug addict, another’s father was shot in the face by US soldiers during a night raid. When the movie is done, the boys will be able to sell it in the streets from their ice-cream carts to support their families. “This is the essence of what the Yellow House is all about,” Gittoes says. “Creativity empowers people.”

The core of Gittoes’ motley crew, however, is Waqar, a fearless cameraman, and three young actors: Neha, a Pakistani soap opera star; Amirshah, a former Taliban sympathizer; and Arshid, also from Pakistan, a little person who crawls all over the artist when we lie back on rugs in the living room after dinner.

Gittoes recalls how he found Arshid at an audition. “I had every midget and dwarf and freak and two-

headed baby in Pakistan in one room,” he says. “And then Arshid walked through the door in a gleam of light.” Gittoes puts his arm around Arshid, who nods and grins. “He’d never acted before but now he’s famous in Jalalabad. He can’t walk outside the Yellow House; he gets mobbed like Michael Jackson.”

That is an exaggeration, but not a huge one. One afternoon, I accompany Amirshah and Arshid to the centre of town to find a child’s suit for Arshid. All eyes are on us: a blond, blue-eyed European attempting camouflage in Afghan robes; Amirshah, who must be the only person in Jalalabad wearing jeans (a habit he picked up on a trip to Australia); and a 35-year-old who is one metre tall. If the people of Jalalabad see the Yellow House as a freak show – which many of them likely would – then Gittoes is its proud ringmaster. “Francis Bacon used to go to the roulette table and blow all his money. I have this place,” he says with a grin.

To Gittoes, the Yellow House is a work of art in itself. Taking inspiration from German artist Joseph Beuys’ idea of “social sculptures”, he believes in the theory of a universal human creativity and in the potential of art to revolutionise society. In a conservative country such as Afghanistan, that translates into pushing cultural boundaries and showing people that it’s not dangerous to do so.

One afternoon, on the lawn in the garden, an ancient Sufi sings and plays the harmonium surrounded by children. Hellen Rose dances and claps and Arshin sings along. Neha, the actress, films everything from the top of a ladder, while Gittoes’ new monkey, Tim Tam, watches the whole spectacle with encouraging chirps. Sufis were persecuted by the Taliban for many years, so bringing the man here to teach children his traditional songs is highly controversial. Equally provocative is the presence of women wearing make-up and without headscarves, dancing around the compound. Everything is out in the open for all the neighbors to hear and there is so much un-Islamic behavior going on that you wouldn’t know where to begin to get offended.

In the middle of it all sits Gittoes, wearing his white skullcap, his face pinked by the afternoon sun. The Sufi beams a toothless smile and plays another song, this time slower so the children can keep up. Gittoes maintains good relations with the neighborhood malik, or chieftain, and occasionally gets a visit from a local leader of the Islamist insurgent group, the Haqqani network. Diplomacy seems to grant Gittoes some measure of protection, but he and Rose have received death threats in phone calls and text messages. When the team films in the streets, crowds will gather. George brusquely shoos them away, in English, which very few people in Jalalabad speak: “Mate, can’t you see we’re filming?”

“Sometimes I worry,” says Amirshah, the ex-Taliban actor. “I know my people. There are many crazies.” At the same time, Amirshah is grateful that Gittoes pushes the limits. “He has helped me a lot. The Taliban used to blow up video stalls.” Now Amirshah is a full-time actor whose films are sold in DVD stalls in town.

Still, despite his ability to defuse situations, Gittoes takes precautions. He keeps a firearm in practically every room of the house. When asked how he can be a war opponent – and now, peace award recipient – and still be armed to the teeth, he says, “That’s a stupid question. That’s the sort of question someone back in Sydney would ask. It’s very easy to a take a philosophical stance over a cup of coffee in Surry Hills.”

Charles Green says Gittoes’ deliberate detachment from the art world and the mythology surrounding him – “of a crazy artist at odds with the cynical art world” – turns some people off his work. In other, less-diplomatic words: perhaps Gittoes would have a bigger following if he didn’t seem so pompous. But perhaps he doesn’t care.

Though he is unlikely to settle in Australia any time soon, Gittoes might be under the impression that it’s time to slow down. He has had prostate cancer surgery and a double knee replacement that makes it hard for him to crouch and been hospitalized for an internal hemorrhage that had him coughing up blood in a New York elevator. He has arthritis in his hands.

At the same time, Gittoes is on a roll of public acclaim. The Australian Financial Review recently highlighted him as a sound art investment, stating that his works, which sell for between $10,000 and $120,000, are undervalued. The State Library of NSW acquired a collection of Gittoes’ diaries, dating from 1987 to 2014, which senior curator Louise Denoon says gives an insight into his work process: “You can see his struggle to represent the horror of war.” She won’t reveal what the library paid for the diaries, but Gittoes says he got $400,000.

His newest film, Love City Jalalabad, won best documentary at the New York Winter Film Awards in February. He is also working on a memoir called Blood Mystic. Meanwhile, another project is simmering. In the evening, as drones hum unnervingly above Gittoes’ house, he flips open a binder of newspaper clippings. “My next canvases are going to be horrific beyond belief,” he says and oints to a photo of militants of the so-called Islamic State preparing to decapitate a hostage. With no lack of horrors to document, Islamic State has got to be the darkest. “I can draw like an angel. I’m one of the best draftsmen in the world and I have got to use that talent,” he says. “Someone has to do it. If anyone is qualified, it’s me.”