Bill Bigelow

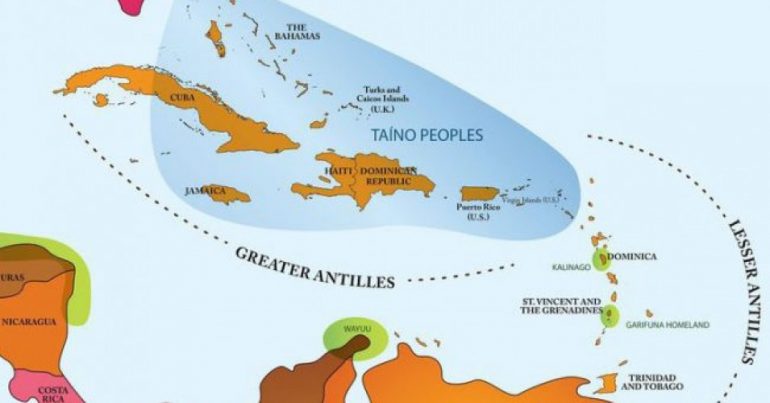

Students Can Name Columbus, But Most Have Never Heard of the Taíno People

Columbus’s treatment of the Taíno people meets the UN definition of genocide. But there has also been a curricular genocide — erasing the memory of the Taíno from our nation’s classrooms

Early in my high school U.S. history classes, I would ask students about “that guy some people say discovered America.” All my students knew that the correct answer was Christopher Columbus, and every time I asked this question, some student would break into the sing-song rhyme, “In Fourteen Hundred and Ninety-two, Columbus sailed the ocean blue” — and others would join in.

“Right. So who did he supposedly discover?” I asked.

In almost 30 years of teaching, the best anyone could come up with was: “Indians.”

I brushed that answer away: “Yes, but be specific. What were their names? Which nationality?” I never had a student say, “The Taínos.”

“So what does this tell us?” I asked. “What does it say that we all know Columbus’s name, but none of us knows the nationality of the people who were here first? And there were millions of them.”

This erasure of huge swaths of humanity is a fundamental feature of the school curriculum, but also of the broader mainstream political discourse. We usually think about the curriculum as what is taught in school. But as important — perhaps more important — is what is nottaught, which includes the lives rendered invisible. Young people, and the rest of us, become inured to the way in which certain people’s lives don’t count, the way in which the world is cleaved in two: between the worthy and the unworthy, those who matter and those who don’t. The “don’t matter” people are the ones the Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano called los nadies, the nobodies — “Who speak no languages, only dialects. Who have no religions, only superstitions. Who have no arts, only crafts.”

My students and I read and talked about this erasure — these horrific attacks on Taínos who might dare “to think of themselves as human beings.” Because Columbus’s policies of enslavement, terrorism, and ultimately, mass murder are so egregious, it’s tempting to focus only on Taíno deaths.

For the Taíno people of the Caribbean, their erasure began almost immediately, with Columbus’s arrival. It was not curricular, it was flesh and blood. “With 50 men we could subjugate them all and make them do whatever we want,” Columbus wrote in his journal on his third day in the Americas. In 1494, Columbus launched the transatlantic slave trade, sending at least two dozen enslaved Taínos to Spain, “men and women, boys and girls,” as he wrote. The next year, 1495, Columbus launched massive slave raids, rounding up 1,600 Taínos, from which the “best” 500, perhaps 550, were selected to be shipped to Spain. Of the hundreds of captives left over, “whoever wanted them could take as many as he pleased,” one eyewitness, a Spanish colonist, Michele de Cuneo, wrote, “and this was done.”

The Spanish priest Bartolomé de las Casas described what he called the “terror” launched by Columbus in his quest for gold and to suppress Taíno resistance:

It was a general rule among Spaniards to be cruel; not just cruel, but extraordinarily cruel so that harsh and bitter treatment would prevent Indians as daring to think of themselves as human beings or having a minute to think at all. So they would cut an Indian’s hands and leave them dangling by a shred of skin and they would send him on saying, “Go now, spread the news to your chiefs.” They would test their swords and their manly strength on captured Indians and place bets on the slicing off of heads or the cutting of bodies in half with one blow. They burned or hanged captured chiefs.

My students and I read and talked about this erasure — these horrific attacks on Taínos who might dare “to think of themselves as human beings.” Because Columbus’s policies of enslavement, terrorism, and ultimately, mass murder are so egregious, it’s tempting to focus only on Taíno deaths. But those deaths can seem abstract and distant, unless we learn something about Taíno lives.

It has always struck me that Columbus himself expressed much more curiosity about the Taínos than one finds in corporate-produced textbooks — although in recent years, no doubt because of Indigenous activism, textbook publishers have discovered the Taínos, if only briefly and superficially. The Taínos were not literate, in the conventional sense, and so wrote nothing about themselves, but Columbus’s journal offers intriguing, if limited, details. In the journal of his first voyage, Columbus wrote about the Taíno people’s homes: “Inside, they were well swept and clean, and their furnishing very well arranged; all were made of very beautiful palm branches.” He said there were “wild birds, tamed, in their houses; there were wonderful outfits of nets and hooks and fishing-tackle.” Columbus writes that it was a “delight” to see Taino canoas (canoes) that were “very beautiful and carved… it was a pleasure to see its workmanship and beauty.” After a little more than three months traveling from island to island, Columbus concluded that the Taíno people are “the best people in the world, and beyond all the mildest… a people so full of love and without greed… They love their neighbors as themselves, and they have the softest and gentlest voices in the world, and they are always smiling.”

Of course, Columbus’s curiosity was grounded in his single-minded quest for gold, and how he might exploit the Taínos to further that mission. As Columbus later wrote King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella: “Gold is a wonderful thing! Whoever owns it is lord of all he wants. With gold it is even possible for souls to open the way to paradise.”

After a little more than three months traveling from island to island, Columbus concluded that the Taíno people are “the best people in the world, and beyond all the mildest… a people so full of love and without greed… They love their neighbors as themselves, and they have the softest and gentlest voices in the world, and they are always smiling.”

Columbus’s portrait of the mild, soft, and gentle Taíno may conceal that they also tenaciously resisted the Columbus regime, once its exploitative and deadly nature became clear. This resistance has been called the first anti-colonial guerrilla war in the Americas. It began as early as Columbus’s first trip back to Spain, when he left 39 Spaniards at his La Navidad settlement, confident that the powerful Spaniards could handle the supposedly timid Taínos. In response to the Spaniards’ rapacity, the Taínos killed all 39 Spaniards, and burned their fort.

If Columbus’s first trip, with three vessels and maybe 100 men, was an exploratory probe, the second trip, with 17 ships and between 1,200 and 1,500 men, was a full-scale invasion. When slavery turned out not to be profitable on la Española (the island that today is Haiti and the Dominican Republic), Columbus instituted a tribute system for the Taínos, demanding quotas of gold and cotton, with sadistic punishments for those who failed to comply. This system was “impossible and intolerable,” wrote Bartolomé de las Casas.