HU Resist

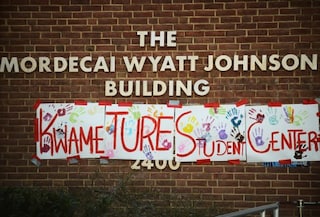

Student protesters at Howard University renamed the school’s administration building the Kwame Ture Student Center, after Howard graduate and civil rights activist Stokely Carmichael, who changed his name after moving to Africa in 1968. (Astrid Riecken for The Washington Post)

Last weekend, on the third day of their takeover of the administration building at Howard University, students spilled out of a lengthy negotiating session with trustees in a jubilant mood.

The meeting had gone well. Progress had been made. And the celebratory exit was accompanied by a buoyant chant.

“Beep, beep! Bang, bang! Ungawa! Black power!” the students sang.

It was not the first time that chant has been heard at a Howard demonstration. In 1968, hundreds of students stood in front of the same building, singing and clapping along to the song, an expression of unity marking their takeover of the hall.

That the song reemerged at this year’s protest, which ended Friday and is the longest in Howard’s history, was no accident. Though the March 29 takeover of the “A” building by several hundred students seemed to come out of the blue, it was actually months in the planning and decades in the making. Organizers of the occupation at the nation’s premier black university say the 1968 protest and another in 1989 informed the strategy and, perhaps more important, the spirit of their action.

Student members of HU Resist, the group that has organized the protest, began discussing the possibility of an occupation in January.

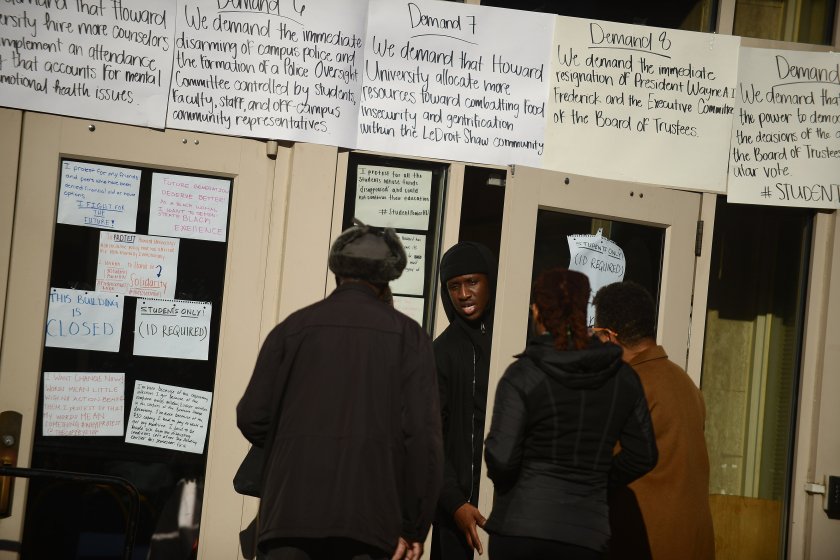

Students occupied the administration building on campus of Howard University to protest the university’s policies, tuition hikes and neglect of student affairs.

CREDIT: The Washington Post via Getty Images

As part of its preparation, members looked to similar student actions that had buffeted the university. They watched “Color Us Black!” — a documentary about the Howard student sit-in that shut down the campus for four days a half-century ago. They read accounts of both events. They spoke with alumni about their tactics and expectations, including the importance of issuing a clear set of demands.

“We do this knowing that we are not the first to do this and we respect that,” senior Alexis McKenney, a protest leader, told reporters. “We’ve had a lot of solidarity from people from ’89 and ’68 saying that they are proud of us for continuing that tradition of student organizing and student activism in holding our university accountable.”

They also noted the political maneuvering of earlier protest leaders, some of whom went on to become formidable politicians. Ewart Brown, the student body president in 1968, became premier of Bermuda from 2006 to 2010. And Ras Baraka, one of the student leaders in 1989, is now mayor of Newark.

Freshman Imani Bryant, another leader of the student demonstrators, said they took cues from their predecessors in every aspect of their rebellion.

“We were trying to learn from them and learn from history,” Bryant said in an interview in front of the administration building Wednesday. The building’s official name is the Mordecai Wyatt Johnson Administration Building, but Bryant and her cohorts had re-christened it the Kwame Ture Student Center after Howard graduate and civil rights activist Stokely Carmichael, who changed his name after moving to Africa in 1968.

What the students wanted to emulate most from their protesting predecessors was the sense of unity and focus those students had, Bryant said. On the first day of the protest, some of those who had taken part in the 1989 occupation stopped by to offer their support. And alumni who participated in the 1968 protest took part in a rally at the building on Thursday.

For Eli Breidford, a transfer student majoring in musical theater, the takeover was an extension and affirmation of what took place in 1968 and 1989.

Some of the issues are the same. Concerns about housing and tuition. Questions about transparency. Demands that students have more of a say in university decisions.

“In ’68, they were calling for self-determination, and we want students to have as much self-determination as possible,” Breidford said. “A big part of it is calling on the school to recenter itself around the student body.”

Jeffrey Fearing was a freshman at Howard in 1968. He remembers students carrying mattresses out of their dorm rooms and into the administration building soon after the takeover. He quickly joined them and would spend the next three nights occupying the hall. Classes were halted, and the university was was essentially closed down.

“There was an air of excitement about it,” said Fearing, who is now retired after a long career as a medical photographer and instructor at Howard. “We were proud of what we had done and what we were doing.”

The students in 1968 issued a number of demands to the administration, including the resignation of the president at the time, James M. Nabrit Jr., an end to compulsory participation in ROTC, and establishment of black American history and cultural programs.

“We wanted to assert ourselves as a black university,” Fearing said. “They were more interested in Howard being a black version of an Ivy League at that point.”

There was great enthusiasm for the protests, but there were significant risks for those who took part. The Vietnam War was raging and full-time college students were exempt from the draft. If the students were expelled, Fearing said, many worried they would be drafted right away.

Fearing said he supports the agenda of the current Howard students other than their demand, since dropped, that President Wayne A.I. Frederick step down.

“I see myself in them and their resolve and the pride that they take in what they’re doing and the mission they set about accomplishing,” he said. “It brings back a lot of very positive memories, and they’ll have these memories for the rest of their lives.”

As in 1968, the March 1989 protest that occupied the administration building was rooted in a call for the university to reassert itself as a black institution. It began when students disrupted convocation ceremonies to protest the appointment of Lee Atwater, then chairman of the Republican National Committee, to the school’s Board of Trustees.

Atwater was an adviser to George H.W. Bush during his 1988 presidential run and helped conceive the racially charged Willie Horton campaign ad that helped Bush defeat Michael Dukakis. Atwater was criticized by students for his record on civil rights issues and his views on apartheid in South Africa.

Students demanded Atwater be removed from the board and also insisted the school institute an African American graduate studies program, improve its financial aid programs and address the deteriorating conditions of campus buildings.

Initially, riot police were called in to remove the protesters, but that plan was blocked by Marion Barry, the D.C. mayor at the time. Instead, Barry and the Rev. Jesse L. Jackson negotiated a deal between the students and the administration.

“We left the table with everything we wanted,” Garfield Swaby, a senior and president of the Howard University Student Association, told The Washington Post after the deal was struck. “If you are right, you will win.”

Swaby, now the head of IT at the New York Public Library, laughed when the quote was read to him over the phone.

“Yeah, that sounds like me back then,” he said. Swaby watched this year’s student occupation with interest and says he is heartened student activism is alive and well at his alma mater.

“Even after all these years, it’s necessary to keep the institution focused on what it’s truly there for,” he said.

Pearl Stewart was a freshman in 1968 and a reporter for the student newspaper, the Hilltop. She sees many similarities in the students protesting today and those who took part then.